I’m reading a book right now that’s got me thinking a lot about my thinking. It’s called, Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. He’s a psychologist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics and is credited with helping to launch the now very popular field of behavioral economics. (It was his recent interview with Krista Tippett that got me to finally get the book off the shelf!)

The book, at its heart, is about the relationship between what the author calls System 1 and System 2 thinking. System 1 is fast. It’s the part of our thinking that sees “2 + 2” and doesn’t have to think about it. It just knows. System 2 is slow. It’s the part of our thinking that goes to work when System 1 doesn’t know what to do with “24 x 17.”

System 1 is always feeding System 2 impressions and conclusions about the meaning and importance of things, sometimes correctly and often not. System 2 is responsible for determining if System 1 is to be trusted and, if not, to seek more information. The dilemma, Kahneman points out, is that System 2 is lazy. It really doesn’t want to do the slower work but will do it if absolutely necessary. It’s very happy to act on System 1’s impulsive reactions.

A personal example to make the point: yesterday, on the way home from a client meeting I received a common spousal text: “Will you please stop at the store and pick up a gallon of milk?” I replied with a “thumbs up.”

As I entered the store it dawned on me that there’s always something else we need so I send another quick text: “Just milk?” As I arrived at the front of the checkout line I received this reply: “Did you use all the celery yesterday? If so, we need some for soup.” And then this, immediately following: “And saltines!”

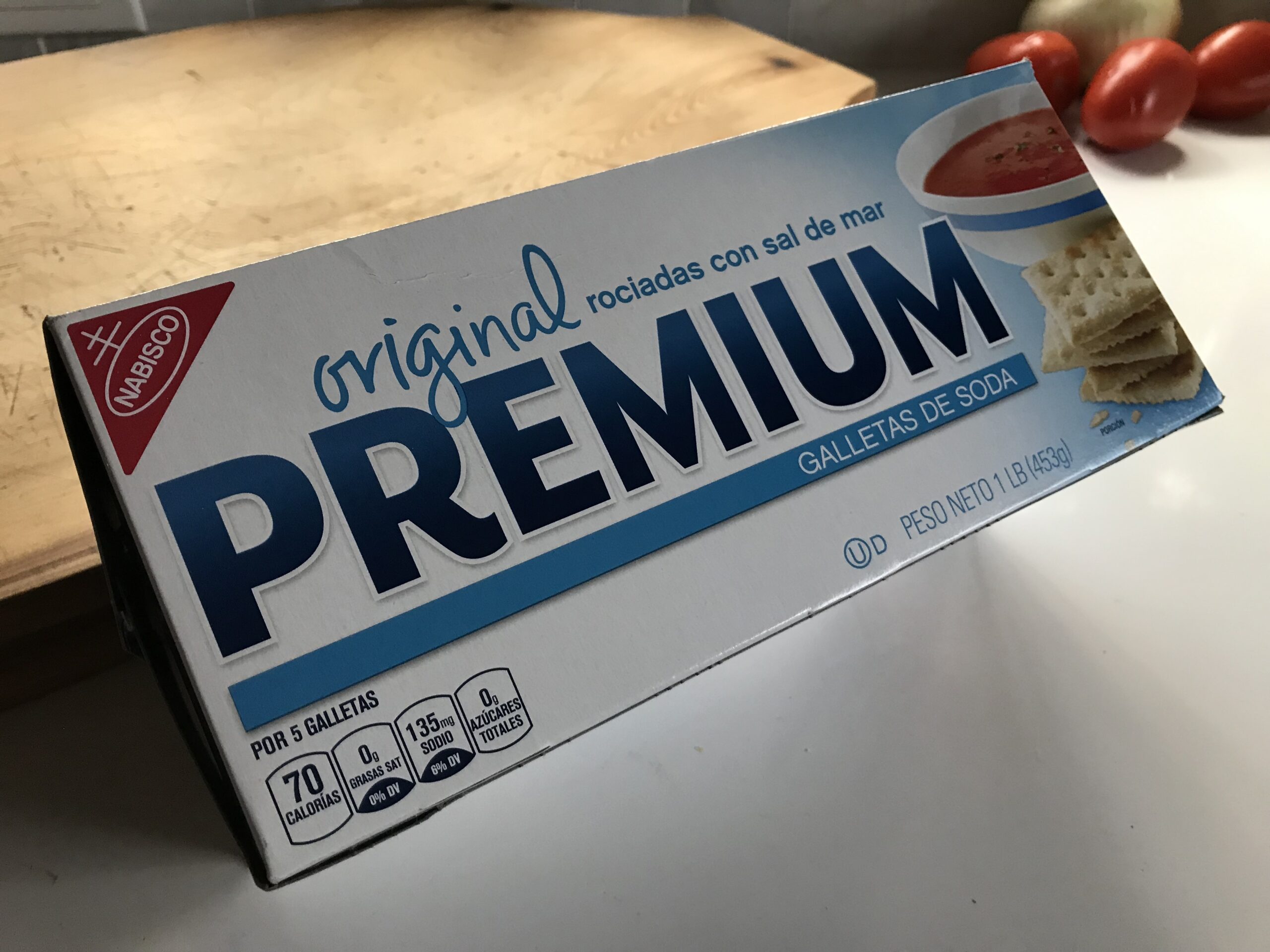

I remembered that we still had some celery, so I asked the cashier to set my milk aside while I went to fetch the Saltines.

Later that evening, as soup was being labeled into bowls, I noticed the still unopened box of crackers on the counter so I asked, “Would you like me to open these?” I was told, “No, we’re having bread.”

Incredulous, I said, “Then why did I leave the front of the line at the grocery store to go back for Saltines?!?”

“Because the girls asked if we could get some,” she said, growing impatient with my tone.

And that’s when the relationships between System 1 and System 2 made sense to me. My System 1 took the well-worn shortcut from “soup” to “Saltines” and my System 2 didn’t even think to question it. But, of course, “soup” isn’t the only possible reason to buy Saltines, it’s just the easiest one. My lazy System 2 wasn’t interested in exerting any extra effort to consider a different possibility.

I took a breath and apologized for my over-reaction. And then I got to thinking about the far more serious and consequential implications of Kahneman’s work and my personal experience of it. If it were just soup and crackers, no problem, but it’s so much more than that. Every day, we are receiving impressions of people and issues and conflicts and every day we are shortcutting our potential for deeper examination and more comprehensive understanding in favor of answers that match our existing models of “normal.”

Once you see what’s going on, you can’t un-see it. If we weren’t so darn lazy we could do so much better.

DAVID BERRY is the author of “A More Daring Life: Finding Voice at the Crossroads of Change” and the founder of RULE13 Learning. He speaks and writes about the complexity of leading in a changing world.